The 10 Most Misunderstood Classic Books (What They're Actually About)

Spoiler: Pride and Prejudice is not a romance novel

You’ve been reading these books wrong your entire life.

Not because you’re a bad reader. Because high school English teachers, SparkNotes summaries, and half the internet have been lying to you about what these books are actually doing.

Let me be brutally honest: Most “classic literature analysis” is academic nonsense designed to make simple books sound complicated and complicated books sound simple.

Here’s what’s really happening in 10 famous classics that everyone gets completely wrong.

Buckle up. Some of these are going to make you mad.

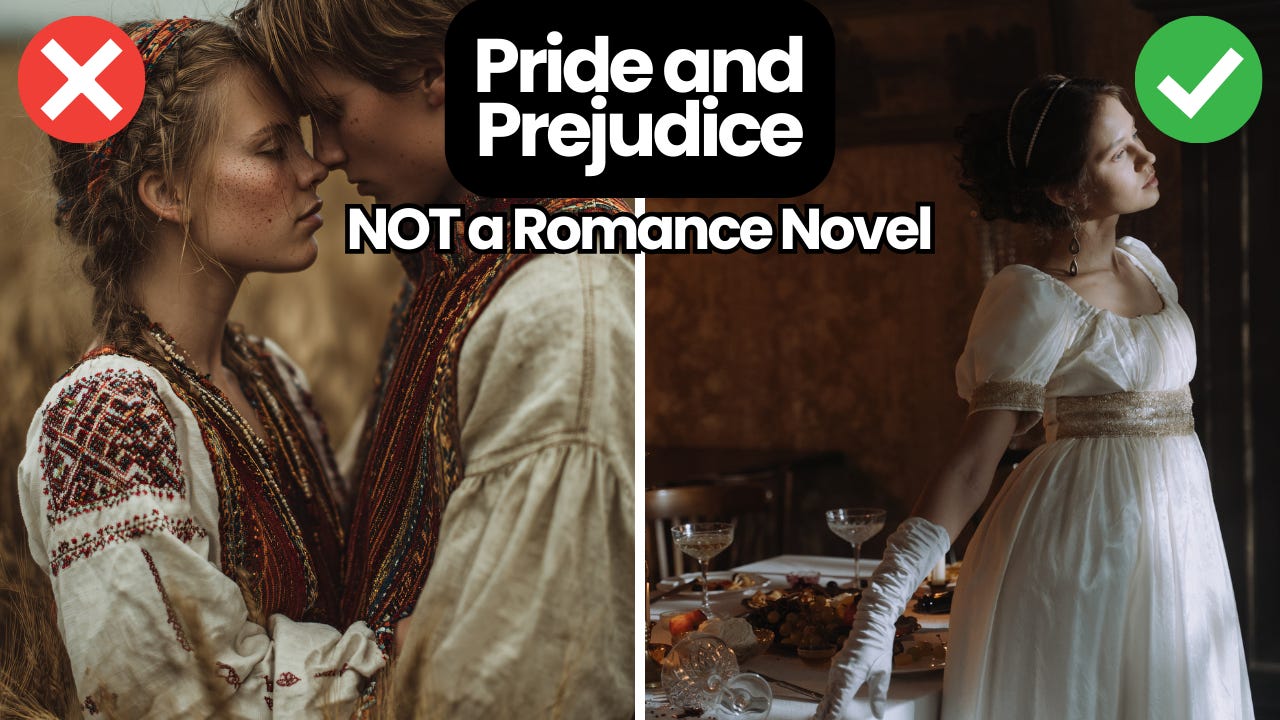

#1: Pride and Prejudice Is NOT a Romance Novel

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Lizzy and Darcy fall in love, overcome pride and prejudice, live happily ever after. It’s Jane Austen’s romantic masterpiece!

What it’s actually about:

Economic survival for women in a patriarchal system where marriage is literally the only career path available.

The “romance” is secondary to the cold, hard reality: If Elizabeth doesn’t marry well, she will be homeless when her father dies. Her mother isn’t “silly” for obsessing over marriages—she’s terrified her daughters will end up destitute.

Every choice in this book is economic:

Charlotte marries Collins for financial security (smart, not tragic)

Lydia’s elopement threatens the family’s social status (and therefore marriage prospects)

Darcy’s wealth is mentioned more than his personality

The “happy ending” is Elizabeth securing £10,000 a year

The real theme: Women making the best financial decisions possible in a system designed to keep them powerless.

Is there love? Sure. But calling this “just a romance” is like calling The Great Gatsby “just a party book.”

Why this matters:

When you read it as romance, you miss Austen’s savage social commentary about women’s economic vulnerability.

#2: Moby-Dick Is NOT About a Whale

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Obsessed captain hunts white whale. Whale wins. The end.

What it’s actually about:

19th-century American capitalism, environmental destruction, and the death of the frontier myth.

Melville wrote an entire book about the whaling industry (the oil industry of its time) to show how American “progress” was built on:

Ecological devastation

Multinational exploitation

The commodification of nature

Religious justifications for destruction

Ahab isn’t crazy—he’s the logical endpoint of American exceptionalism. If you believe you have a divine right to dominate nature, you end up like Ahab: destroyed by what you tried to conquer.

The real theme: Capitalism will literally destroy the world (and everyone on the ship) in pursuit of profit and revenge.

Why this matters:

Moby-Dick predicted climate change in 1851. It’s not a boring whale book—it’s a 700-page warning we ignored.

#3: The Great Gatsby Is NOT About the American Dream

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Poor boy loves rich girl, gets rich, throws parties, dies tragically. The American Dream is dead.

What it’s actually about:

The American Dream was always a lie designed to keep poor people working for rich people’s benefit.

Gatsby didn’t fail to achieve the American Dream. He achieved it perfectly—and discovered it was empty, corrupting, and built on exploitation.

The book’s not saying “the Dream died.” It’s saying “the Dream was always a con.”

Key detail everyone misses:

Gatsby got rich through organized crime. The only way to “make it” in America is through corruption. That’s not the Dream failing—that’s the Dream working exactly as designed.

The real theme: American meritocracy is a myth. Class mobility is nearly impossible, and even when you “make it,” you still don’t belong.

Why this matters:

If you read this as “sad rich people problems,” you miss Fitzgerald’s entire point about class and inequality.

#4: Frankenstein Is NOT About a Monster

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Mad scientist creates monster, monster is evil, everything goes wrong.

What it’s actually about:

What happens when you abandon your responsibilities and refuse to take care of what you created.

The creature isn’t born evil—he’s abandoned, abused, and rejected by every human he meets, including his own creator.

Key detail: The creature is intelligent, sensitive, and deeply lonely. He becomes “monstrous” only after society treats him as a monster.

The real theme: Creators are responsible for their creations. If you bring something into the world and abandon it, you’re the monster, not it.

Modern application: This is about:

Parental neglect

AI ethics

Corporate responsibility

Environmental destruction

Any technology created without thought for consequences

Why this matters:

Victor Frankenstein is the villain. The “monster” is the victim. Mary Shelley knew what she was doing.

#5: Wuthering Heights Is NOT a Love Story

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Heathcliff and Catherine are soulmates torn apart by society. Gothic romance! Passion! Moors!

What it’s actually about:

Generational trauma and how abuse repeats itself across families.

Heathcliff and Catherine are toxic, abusive, and destroy everyone around them. Their “love” is obsession, revenge, and mutual destruction.

Key detail: Emily Brontë is not asking you to root for Heathcliff. She’s showing you how abused children become abusive adults who pass trauma to the next generation.

The real theme: Revenge and obsession destroy everything. You cannot heal trauma by inflicting it on others.

Why this matters:

If you read this as “romantic,” you’re romanticizing abuse. Brontë was critiquing destructive relationships, not celebrating them.

#6: 1984 Is NOT About Totalitarianism (Only)

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Big Brother is watching. Government bad. Dystopia warning.

What it’s actually about:

How language controls thought, and how destroying language destroys the ability to resist.

Everyone focuses on the surveillance state. But Orwell’s actual innovation was Newspeak—the idea that if you eliminate words for “freedom,” “rights,” and “justice,” people literally cannot think those concepts.

Key detail: The appendix about Newspeak is the most important part of the book, and everyone skips it.

The real theme: Control language, control reality. If you can’t name something, you can’t fight it.

Why this matters:

1984 isn’t about cameras and secret police. It’s about how power uses language to make resistance literally unthinkable.

#7: Jane Eyre Is NOT About Female Independence

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Jane is a strong, independent woman who chooses love on her own terms. Feminist icon!

What it’s actually about:

A woman who can only achieve “independence” after she inherits money from a dead relative.

Key detail everyone forgets:

Jane refuses Rochester the first time because she has no money and would be dependent on him. She only comes back after she inherits wealth and can marry him as an equal.

The real theme: Women’s “independence” in Victorian England wasn’t about strength or feminism—it was about money. Without financial independence, personal independence is impossible.

Why this matters:

Jane Eyre isn’t proving women can be strong—it’s proving women need economic power to have any power at all.

#8: Lord of the Flies Is NOT About Boys Being Evil

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Put boys on an island, they become savages. Humans are naturally evil. Civilization is a thin veneer.

What it’s actually about:

What happens when you raise boys in a militaristic, authoritarian culture and then put them in a survival situation with no adults.

Key detail: These aren’t random boys—they’re British boarding school students in the 1950s, raised in an intensely hierarchical, violent, colonialist culture.

The real theme: The boys don’t become savage despite civilization—they become savage because of what civilization taught them.

Why this matters:

In real-life cases of kids stranded on islands, they cooperated, shared resources, and survived together. Golding’s pessimism says more about British colonialism than human nature.

#9: The Scarlet Letter Is NOT About Adultery

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Hester Prynne commits adultery, wears scarlet “A,” learns her lesson about sin.

What it’s actually about:

How religious communities use public shaming to control women while protecting powerful men.

Key detail: The father of Hester’s child (the minister) faces zero consequences. He’s protected by the same community that destroys her.

The real theme: Religious moral codes are enforced selectively to maintain power structures. Women are punished for “sins” that men commit without consequence.

Why this matters:

The book isn’t about Hester’s sin—it’s about a community that punishes women to maintain control. Hawthorne was critiquing Puritan hypocrisy, not endorsing it.

#10: Animal Farm Is NOT Just About Communism

What everyone thinks it’s about:

Communism bad. Russian Revolution allegory. Pigs = Stalin.

What it’s actually about:

How ALL revolutions get corrupted when new leaders replicate the power structures they overthrew.

Key detail: Orwell wasn’t saying “communism bad, capitalism good.” He was saying power corrupts any system, including socialist ones.

The real theme: Revolutionary movements fail when they prioritize power over principles. The problem isn’t the ideology—it’s that power-seeking people will corrupt any ideology.

Why this matters:

If you read this as “communism = evil,” you miss Orwell’s actual target: authoritarianism in any form, including in democracies and capitalist systems.

The Pattern You’re Not Supposed to Notice

Here’s what all these misreadings have in common:

They make the books safer.

Less political. Less economic. Less about systems of power.

“Pride and Prejudice is romance!” is easier than “Austen was critiquing women’s economic oppression.”

“Frankenstein is about monsters!” is simpler than “Frankenstein is about corporate responsibility.”

The truth:

Classic books are “classic” BECAUSE they’re challenging, political, and uncomfortable.

If your interpretation makes the book cozy and simple, you’re probably missing the point.

Your Turn: What Have I Got Wrong?

I want to hear from you in the comments:

Which of these made you angry? (Be honest, I can take it)

What classic book do YOU think everyone misreads?

What’s a hot take about a classic you’re afraid to say out loud?

Drop your opinions below. Let’s fight in the comments like literature nerds should.

My Free Gift For You:

What if you could finally finish the classics—without the guilt, pressure, or burnout?

With just 12 pages a day, you can read 9 classic books in a year—even if life feels full and your TBR list overwhelms you.

✨ I created a free guide just for you:

All new Literary Fancy subscribers receive the guide in their welcome email. Already a subscriber and didn’t get it? Just reply to this post or message me—I’ll send it your way!

Literary Fancy is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Share your hot take: What classic does everyone completely misunderstand?

Affiliate disclosure: Book recommendations and links in this post may be affiliate links. Hot takes are always free.

Not angry, but I do have a few notes:

+ "[Mrs Bennet] isn’t “silly” for obsessing over marriages" Well... she is *kinda* silly. What the "Mrs Bennet was right all along!" view tends to overlook / oversimplify is that while Mrs Bennet is not *wrong* that her daughters need to marry well, what makes her silly is that she views "marrying well" as the be-all end-all to the point where she treats her own daughters as essentially commodities to be traded to ensure her own comfort (and it is *her own* comfort; most of her concern about the situation is expressed in the form of whining about how it will affect *her*), leading to a situation where her single-minded focus on "get them married and everything will sort itself out" actually sabotages her own goals and makes things worse most of the time. Her discussing men as if they were stud horses to be traded just puts said men off, she cares about the "marrying well" part but not the "raise my daughters well so that they will be attractive to prospective husbands in the first place" part, and the way she simpers and coos over Mr Wickham and Lydia's marriage despite the fact that it in no way, even by her standards, a successful match (for one: he doesn't have enough money to support them all) clearly demonstrates that this is not the sensible and practical-minded woman soberly facing the realities of her daughter's situation that modern readers tend to paint her as. Miss Austen is indeed savagely targeting the economics of the day, but what people tend to forget these days is that Mrs Bennet is in no way spared any of the venom. She is a stopped clock, not a secret hero.

+ "Orwell wasn’t saying “communism bad” Well... he kinda was. At least, the "Communism as expressed in its mid-20th century Stalinist form" version was bad. "Animal Farm" can definitely be read as anti-totalitarian in general, but the parallels to Soviet Russia are screamingly obvious and absolutely intended. Orwell's big project for most of his life was basically yelling in the face of his fellow socialists that Stalin wasn't good just because he was nominally on 'their' side, and that communism in practice wasn't the communism his fellow travellers yearned for just because its leaders parroted the correct shibboleths. (The "capitalism good" bit, I'll grant you that one.)

None of these made me angry. Thanks for your explanation of Wuthering Heights, I never enjoyed reading that book and now I understand why. Never read Moby Dick, maybe that will be this year’s project now that I have a better understanding of the meaning.